Can art furries solve climate change?

Protest art has to work as art to work as protest.

Climate activism has returned to the Art Gallery of Western Australia (AGWA) – only this time, with the institution’s seal of approval.

In January last year, my friend Joana Partyka prompted headlines and controversy when she spray painted a Woodside logo over Frederick McCubbin’s iconic painting Down on His Luck in a protest at AGWA against Woodside’s emissions and ongoing destruction of the Murujuga rock art.

Now, Western Australian “tactical media art group” pvi collective have installed their protest work The Social Licence Watchdogs at the gallery in an attempt to shine a light on Woodside and other big emitters.

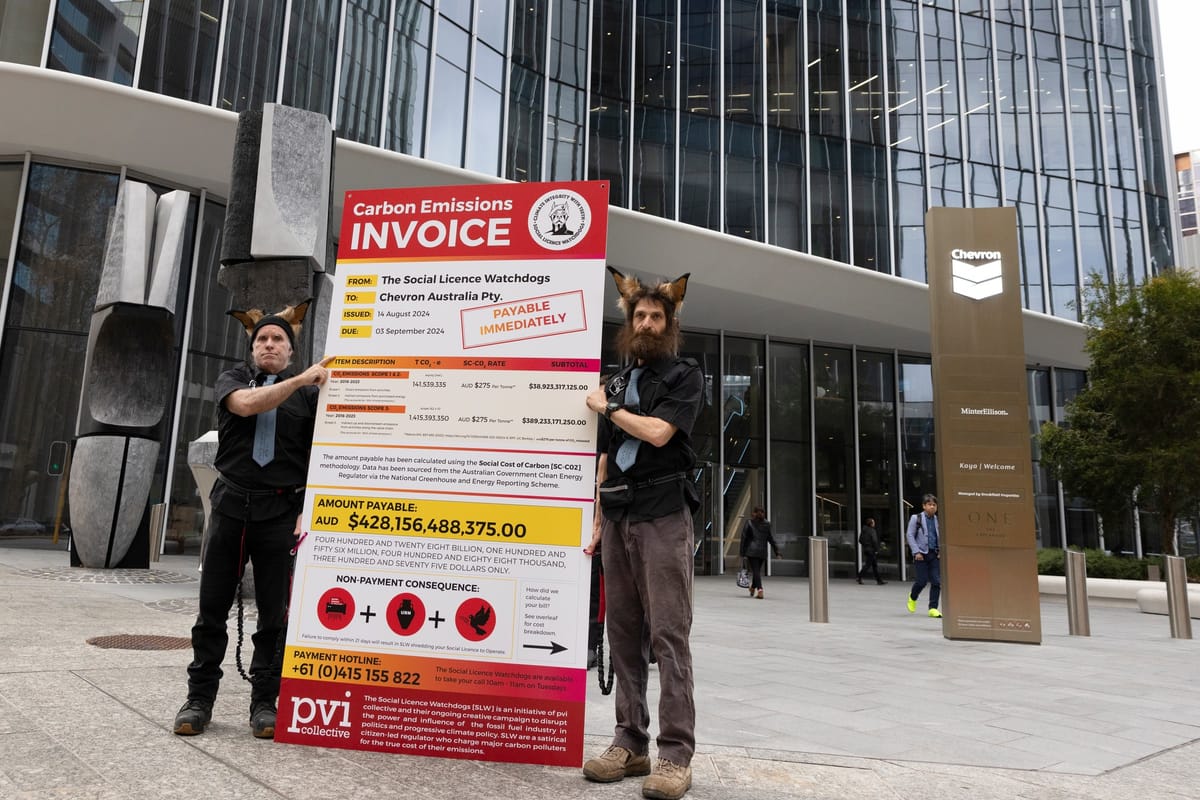

I visited AGWA on Friday and found myself facing five large posters from the pvi collective hanging from the ceiling. Each printout was a “Carbon Emissions INVOICE”, made out to a resources company that operates in Western Australia. The invoices were previously delivered to the headquarters of each company by people wearing costume dog ears (the ‘social licence watchdogs’.) Watching social media videos of these stunts was like watching a lightweight version of The Chaser’s War on Everything, if the Chaser boys also happened to be furries.

In his provocative book The End of Protest, Occupy Wall Street co-founder Micah White calls for coordinated mass marches to be retired from the activist repertoire, believing them to have been proven ineffective by the massive yet unsuccessful anti-Iraq War demonstrations. In a similar vein, I propose a ban, or at least a temporary moratorium, on climate protesters dressing up as animals (and I say this as someone who was once arrested for blocking a road in a polar bear costume.) Cutesy, carnivalesque stunts are easy to put in an aesthetic box of ‘activists doing their thing’ and are unlikely to have much appeal to anyone but the converted. For protest art to cut through, it must have the shock of the new and the ability to destabilise established narratives and battle lines. It needs to transcend cliches, not reinforce them.

My immediate impression upon seeing the exhibition was of death by infographic. Outside of a novel, I’d never seen an artwork with such a high word count. Each invoice showed the working used to reach an ‘amount payable’ as compensation for the social price of carbon. In case anyone mistook these for real invoices, every single printout also included the disclaimer “[The Social Licence Watchdogs] are a satirical citizen-led regulator who charge major carbon polluters for the true cost of their emissions.” I was stunned to read towards the bottom of each card, “See overleaf for cost breakdown.” Indeed, the invoices also had a whole second side of figures, graphs, and words. Then there was all the exegesis, spread across three explanatory panels, from which I learnt that the invoices were both “conspicuously large” and “comically large”, though it seemed to me the viewer should perhaps be the judge of the latter. Next to the printouts was an urn made by Perth artist Abdul-Rahman Abdullah, which will apparently house the companies' shredded 'social licenses' if and when the bills go unpaid.

Good on the pvi collective for calling out fossil fuel corporations directly in a gallery space – especially given that so many of our cultural institutions are often used to build the social licence of big polluters (though not, it should be said, the AGWA, which doesn’t accept fossil fuel sponsorship). I just wish The Social Licence Watchdogs had a bit more bite. I’d like to see pointed anti-fossil fuel artwork at the AGWA that left a stronger aesthetic impression and did something unexpected.

Internal AGWA documents seen by The Last Place on Earth suggest the gallery had plans in place for the possibility the work would attract negative public attention. An F.A.Q document distributed internally and provided to the office of Arts Minister David Templeman included as “key messages”: “This work is a legitimate art form, and consistent with our role to allow artists to talk to the issues of the day … As the State Art Gallery, AGWA has a wide range of audiences form [sic] different backgrounds, cultures, attitudes and needs. It takes its role seriously to provide a forum for diverse, inclusive and relevant discussion.” Of course, in WA, one must exercise caution in criticising the fossil fuel industry. If I were pvi collective, I would have hoped for a bit of controversy to boost the profile of the installation, but I’m not surprised it never attracted the attention of Seven West Media. If you want The West to talk about your protest, you’ve got to serve them up something so juicy they can’t resist.

The thing about protest art is that it's going to have to work as art if you want it to work as protest. I think that on both counts, Joana’s act of vandalism last year beats the pvi collective’s installation hands down. Visually, her performance piece was instantly compelling. It took an existing meme – activists vandalising artwork – and transformed it by adding something new, through the symbolism of the acid-yellow Woodside logo and the implied comparison between Australia’s colonial art and ancient Aboriginal heritage. And it left the audience conflicted: no one wants to see artwork ‘destroyed’, and yet it was hard not to acknowledge Joana was doing something important in her performance. (The cultural value of the protest appears to have been recognised by the WA Museum, which The Last Place on Earth understands has acquired the perspex sheet that protected the McCubbin painting from the spray paint.)

The pvi collective are in the unfortunate position of having The Social Licence Watchdogs installed right in front of Brett Whiteley’s extraordinary mixed media work The American Dream. Just about anything would pale in comparison. Whiteley’s large work, made in 1968 and 1969, has been held in the AGWA collection since 1978 and was recently put back on display. I wouldn’t call it protest art exactly, but it’s definitely political art, referencing the Vietnam War and reflecting the tumult, violence, spirituality, sex, beauty, and horror of 1960s America. It’s immersive and moving, and does for the political mind what the best art can do: provide space for contemplation, where something unexpected might arise.

It might be unfair to compare The American Dream to The Social Licence Watchdogs. Whiteley’s seem to be lofty artistic ambitions, to synthesise and reflect on various maelstroms raging both around and inside him. The pvi collective’s aims are much more straightforward, and they're trying to send an easily graspable message. Still, this kind of work can aspire to offer an engaging aesthetic experience, instil a sense of mystery, and expand the viewer and their thinking in some way.

Outside the gallery, protests on the streets or elsewhere always involve some degree of art and performance. There are lessons here too for activists who see their work primarily in political rather than artistic terms. Lord knows I’ve been involved in more than my fair share of cringe protest stunts, so perhaps I’m the last person who should be throwing stones. But I ask those trying to do something about the climate crisis: please can we try some new things? And before we embark on a project, can we consider whether it has any possibility of actually moving the needle?

The Social Licence Watchdogs is on display at the Art Gallery of Western Australia until 9 September. The American Dream is on display until 8 December.