Notes from an inquest

A coroner's inquest into the death in custody of an Aboriginal teenager has sparked calls for justice.

For the past three weeks, the family of a 16-year-old Aboriginal boy who died in the custody of the state have sat in a Perth courtroom and listened.

The coronial inquest into the death of Cleveland Dodd concluded its second tranche of hearings on Friday, following the first sitting in April.

Dodd died inside Unit 18 of the maximum-security Casuarina adult prison in October last year. Unit 18 was hastily set up in June 2022 as a second youth detention facility in Western Australia, in addition to Banksia Hill Juvenile Detention Centre. Extended lockdowns, staff shortages, self-harm incidents, and violence have plagued both facilities.

For years, many have warned of a crisis in Western Australia’s youth prison system, including former Australian of the Year and Telethon Kids Institute founder Professor Fiona Stanley, who gave evidence to the inquest on Thursday afternoon at the Perth Magistrates Court.

“These children are not the problem,” she said. “The system is the problem.”

Professor Stanley’s evidence lasted hours. She spoke passionately, sometimes furiously, and at one point in tears. She called for a whole-of-government response to the detention crisis and said politicians must “attempt to understand developmental pathways that result in damaged children.” She said WA had produced world-leading research and data on the issues facing children in detention, but it was being ignored by decision-makers.

Repeatedly, Professor Stanley made the point that Aboriginal people needed to be involved in their own affairs: in health, in research, in the justice system, and in the very inquest she was speaking at. “If you employ Aboriginal people, the best results will come – from a research project or from a service,” she said. Aboriginal people sitting in the back of the room nodded in agreement.

She told the coroner she’d reached out to former Premier Mark McGowan and other government ministers multiple times in recent years to discuss her concerns about Unit 18 but had received no meaningful response.

I’d first arrived in the courtroom earlier in the day, as another witness, former Department of Justice Director General Adam Tomison, was being examined. One security officer was patrolling the corridor outside. A second was stationed inside the door. As I entered, he asked me who I was and where I was from.

Dr Tomison was taking the stand for the second time during the inquest. He answered detailed questions about his correspondence and meetings in 2022 and the department’s “strategic communications” plan for public messaging on Unit 18.

It was a familiar courtroom environment: lawyers sat in rows under artificial lighting, lever arch files were piled up on the ground and in trolleys, documents were passed back and forth. We heard details of the department's administrative processes. As I listened, I sat near a mother who would never see her son again. Earlier proceedings had revealed there were four children still locked up in Casuarina’s Unit 18.

While the court broke for lunch, I sat in a café across the road with my friend Desmond Blurton, a Ballardong Noongar man and Deputy Chair of WA’s Deaths in Custody Watch Committee. Des had walked out of the inquest the previous day, along with the boy’s family and other supporters, after the coroner had refused a request from Dodd's mother to bring Bill Johnston before the inquest.

“Justice is not being served,” Des told me. “Bill Johnston was a Minister under L-A-W, but under L-O-R-E, our lore, that’s been here for 60,000 plus years, he is just someone who is occupying our land and making decisions about our people and our children. So he has a responsibility to the community, to the Aboriginal community especially, to speak what he should be speaking about, and that is the truth.”

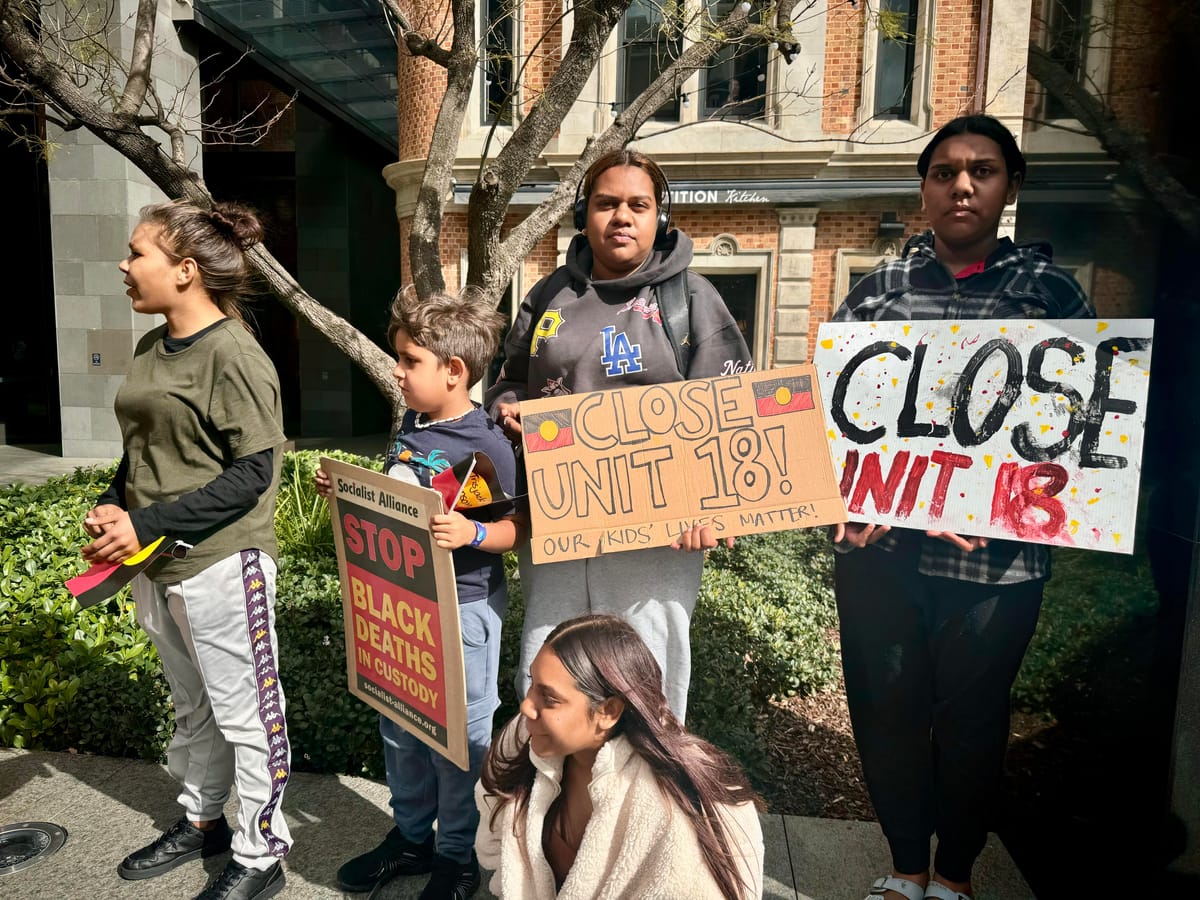

On Friday, the final day in this round of hearings, I joined a rally of around 100 people outside the courthouse. Many of those who’d sat silently inside for weeks now had a chance to speak, their words ringing out across the street from a portable PA. Their message was clear: It was time for action, and Unit 18 needed to be shut down immediately.

“I am sick and tired of inquiries – one after the next, after the next, while our kids are dying, while our kids are taking their lives, while our people are dying on the streets,” Menang Noongar leader and advocate Megan Krakouer said.

On Wednesday, Corrective Services commissioner Brad Royce told the coroner he would advise the government to keep Unit 18 open until a new facility could be built. He estimated that would take between two and five years.

Inquest hearings will continue in October before a final report is prepared.

“I’m hoping that this coroner’s report will be a catalyst for change,” Professor Stanley said as she concluded her evidence on Thursday.

“The thing that would make me feel devastated is if this report sat on the shelf and nothing got done.”