The land of opportunity?

It’s good to learn from your mistakes – but it’s better to learn from someone else’s.

My late great-uncle used to say: “It’s good to learn from your mistakes, but it's better to learn from someone else’s.”

In that spirit, the world should be paying close attention to the ongoing failures of what passes for progressivism in the United States of America. The Democratic Party and the liberal elite have repeatedly failed to understand or address the structural problems that led to the reelection of Donald Trump – and for all their communications consultants and PR professionals, don’t know how to speak to people.

If Trump’s appointments thus far are anything to go by, his second presidency is looking every bit as cruel and disastrous as was widely predicted. For the climate, for Gazans, for workers, for women, for democracy, there appear to be dark times ahead. But, as ever when things change, we should be alert to new opportunities. 2016 could have been an aberration, but 2024 shows we’re witnessing a meaningful shift. Orthodoxies and institutions have fallen. We live in a new world.

Ahead of elections in Australia next year, campaigners of all stripes should be looking to learn from what’s happened in the US. From Western Australia, the last place on earth where anything ever happens, it makes sense to look to the centre of the universe to work out where things are headed.

Electorally in Australia, we’re at an advantage, because our two major parties are less entrenched and we have preferential voting. In other words, anti-establishment rage can be directed somewhere other than the major party duopoly.

Here are four lessons I’m taking from the US election – with a reading list to accompany each:

‘Authenticity’ trumps truth

Donald Trump’s election has shown that voters want authenticity in their political leaders. I’m sure some readers will balk at that sentence – after all, Donald Trump is an inveterate liar who seemingly stands for little other than gratifying his own ego and lining his own pockets. His supporters know he’s a liar, but they don’t care, because to them, on a deeper level, he represents realness. Of course, it's a performance, but not entirely. His unique quirks and preferences are always on display. His love of ‘YMCA’ and ‘Ava Maria’ surely didn’t come from a focus group. He’s a conman and a huckster, but he manages to pull it off because of his vivid, unfakeable personality. Like all the best conmen, he makes being conned an enjoyable experience, even when the victim knows deep down what’s going on.

Think also of the people Donald Trump surrounded himself with during this campaign: Elon Musk, Robert F. Kennedy, J.D Vance, Tucker Carlson, Laura Loomer – they’re all freaks. But the Democrat’s approach of calling them weird didn’t work, because at the end of the day, voters preferred interesting weirdos to dull automatons or out-of-touch A-listers.

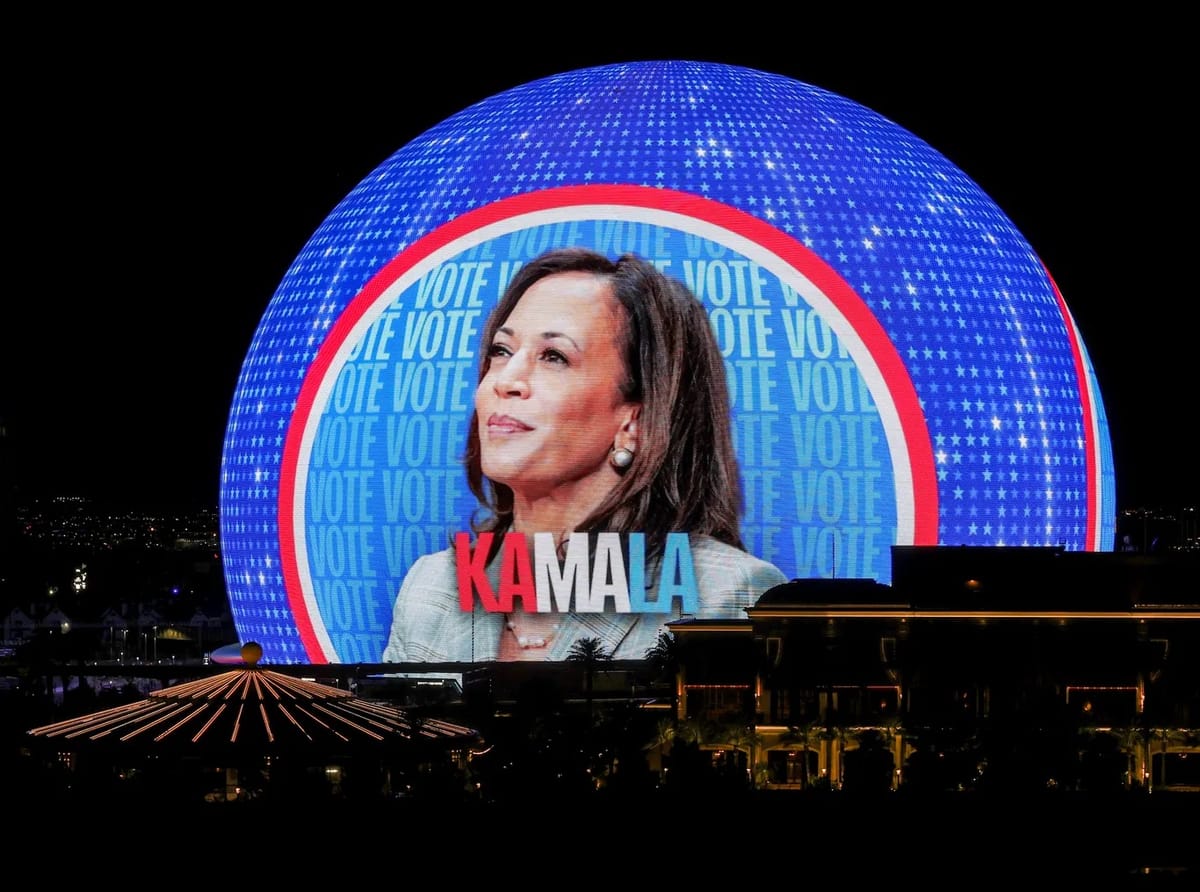

Meanwhile, the Democrats couldn’t claim to have truth or authenticity. The big lie, maintained for so long, was that Joe Biden was fit to run for re-election. Fact checkers show there were smaller lies too. But more importantly, the Democrats just seemed phony.

There’s a telling anecdote in a recent New York Times profile of content creator Kareem Rahma. He interviewed Harris for his TikTok talk show Subway Takes, where guests present controversial opinions. The interview, which Rahma was dubious about in the first place because of Harris’s position on Gaza, was never used. As per The New York Times:

What happened was a dispute over Harris’s take. Rahma said he had been told that the vice president would be taking a stand against removing one’s shoes on airplanes. When they sat down, however, Harris had surprised him with a different take: “Bacon is a spice.” (Two senior campaign officials said this topic had been raised in advance. Rahma and his manager dispute this.)

Rahma, who doesn’t eat pork for religious reasons, was taken aback. “I don’t know,” he says, in an unpublished video recording of the interview, his voice rising to an unusually high pitch. Harris elaborates that bits of cooked bacon can be used to enhance a meal like any other seasoning. “Think about it, it’s pure flavor,” she says.

Rahma asks Harris if he can use beef or turkey and what kinds of dishes would benefit from bacon. He then pauses the interview and tells her that he doesn’t eat it. He asks if they can do the airplanes take instead. But, on the advice of a staffer, Harris decides to declare her love of anchovies on pizza — an alternative the campaign had floated earlier in an email. Rahma wraps the discussion one minute later.

“Well,” he says, with an awkward laugh. “I’m 100 percent unsure on both of those.”

It’s hard to know whether Harris actually believed these ‘takes’, which were clearly workshopped by staffers and comms ‘experts’. The irony is that no staffer realised it would be awkward to talk about bacon with a Muslim man horrified by the genocide being enabled by the Biden/Harris administration. Aside from that, can you imagine Donald Trump needing an aide to recommend an opinion about pizza toppings for him? The guy has takes for days, which were free-flowing during campaign rallies and on podcasts.

The lesson here for campaigners, especially public spokespeople: Be yourself and use your personality. Speak from the deepest and realest parts of your being. ‘Professional’, slick, and soulless are out. Real, messy, and unscripted are in. Be human.

On a related note: Don’t focus so much on debunking misinformation. This is a particular preoccupation of the climate movement, but I’m convinced it's a dead end. Feelings don’t care about your facts. Gain people’s trust by being real and speaking to their real concerns. Tell the truth, yes, but tell it as part of a story. Make your story better than your opponent’s. Connect.

Further reading:

- ‘Notes from a classroom’ by Ian Williams.

- ‘Obsessing Over Climate Disinformation is a Wrong Turn’ by Holly Buck

Traditional media is over

It’s been widely unpacked, including last week in The Last Place on Earth, that this was the content creator election. As has long been predicted, new media has overtaken traditional media as the dominant sphere of mass communication. Much has been made of Trump’s willingness to sit down with bro-casters for sprawling conversations. These long-form appearances were then cut up into viral TikTok videos that went far and wide. While analysis has largely focussed on Trump’s online appeals to men, there’s also a robust online ecosystem of MAGA-adjacent creators in wellness and influencer spaces that appeal largely to women, including House Inhabit (who I became aware of when she played a supporting role in the RFK/Olivia Nuzzi saga), and Trump's granddaughter Kai, who has developed a large TikTok following.

I’m convinced the most important political battleground nowadays is online, and that we're fighting a narrative war. In Australia, the right doesn’t have the same advantage as it does in the US of having more advanced new media infrastructure, though we’re still embedded in the global ecosystem. It should become an urgent project of the Australian left to build platforms and networks for making and distributing good memes.

Further reading:

- ‘“We need a Liberal Joe Rogan”’ by Joshua Citarella (Citarella has been my best guide to the future. I highly recommend his Substack and classic essay ‘Politigram and the post-left’)

- “Why democrats won’t build their own Joe Rogan’ by Taylor Lorenz

- 'the left can't meme report' by Brad Troemel

Ontological materialism is weird and elitist

Trump’s win shows it’s deeply appealing to frame politics as an expression of spiritual warfare. The election might have been over when that bullet missed Trump’s head through seemingly divine intervention, if it hadn’t been over already. Tucker Carlson, meanwhile, who is one of the most widely listened to podcasters on the planet, claimed during the home stretch before the election to have been mauled by demons in his sleep.

Of course, religion is a more important part of life and politics in the US than it is here, but I think it’s wrong to think that Australians don’t connect to spirituality in politics. When I saw Carlson live at the Perth Convention Centre back in June, I wrote about how the crowd lapped up his talk of spiritual warfare.

Most people think of their lives, to some degree, in spiritual terms. The liberal elite reject this in favour of an overreliance on data, logic, and technocratic solutions. The far left often reject it in favour of rigid orthodoxy. It's more appealing to understand the world in terms of concepts like good, evil, conscience, karma, vocation, and purpose – especially in times of existential crisis. In the words of Bob Dylan, you’ve gotta serve somebody.

One of the key contributions of Extinction Rebellion to the climate movement was its framing of the climate crisis as a spiritual challenge. (First Nations activists also excel at this.) The broad climate movement will go further if it keeps exploring that path than we’ll get by fixating on facts and figures.

Further reading:

- ‘Trump’s Believers See a Presidency with God on Their Side’ by Elizabeth Dias and Ruth Graham

- ‘Lessons from Extinction Rebellion: origins’ by Douglas Rogers

- ‘XR XL?’ by Roger Hallam

The vibes have shifted

It’s been apparent for some time now, but the election result solidified it: The vibes have shifted. One way of understanding it is as a cultural shift towards conservatism: Smoking is cool again, skinniness is back on runways, Gen Z slang largely comes from the far-right manosphere (as I wrote about earlier this year), and there’s been an explosion of conservative-coded fashion microtrends like the mob-wife aesthetic, quiet luxury, and various iterations of trad.

Part of the vibe shift is doomerism: People have given up on things getting better. Defeatism and apathy on climate change abound.

Another part of the vibe shift is a rejection of identity politics. Putting your pronouns in your bio is out. The Democrats recognised this (little was made by the campaign of Harris’s race or gender), but it was too little too late to undo their associations with wokeness, which MAGA constantly reinforced and exaggerated.

I sense that this new cultural paradigm and the shift to authenticity create ripe conditions for an emergent Bernie Sanders-inspired politics based on addressing economic inequality. This politics can tap into an aspirational culture by aspiring for more prosperous conditions for ordinary folk. It can avoid being distracted or divided by the niche fixations of identity politics, like it might have been in recent years, without foregoing a commitment to human dignity. In the US, if the second Trump presidency fails to deliver improved economic conditions, the left must capitalise.

Here in Australia, we need to present the issues we care about clearly and plainly, with a focus on how they impact people’s economic realities and everyday lives.

Further reading:

- ‘VIBE SHIFT AMERICA’ by Sean Monahan (who invented the term ‘vibe shift’)

- ‘This Is the Trump 2.0 Aesthetic’ by Makena Kelly

- ‘Postcapitalist Desire’ by Mark Fisher

- ‘The Democratic Elite Should Resign’ by Marianne Williamson

- ‘Bernie Sanders Statement on the Results of the 2024 Presidential Election’